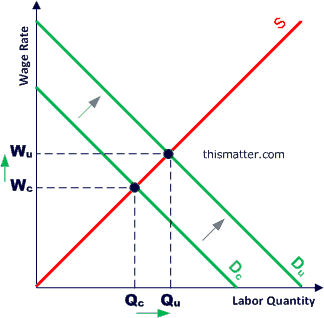

class: center, middle, inverse, title-slide .title[ # Overview of Greenstone, Hornbeck, and Moretti (2010) ] .subtitle[ ## GHM (2010) ] .author[ ### Hussain Hadah (he/him) ] .date[ ### 06 February 2025 ] --- layout: true <div style="position: absolute;left:20px;bottom:5px;color:black;font-size: 12px;">Hussain Hadah (he/him) (Tulane) | GHM (2010) | 06 February 2025</div> <!--- GHM (2010) | 06 February 2025--> --- class: title-slide background-image: url("assets/TulaneLogo-white.svg"), url("assets/title-image1.jpg") background-position: 10% 90%, 100% 50% background-size: 160px, 50% 100% background-color: #0148A4 <style type="text/css"> /* Table width = 100% max-width */ .remark-slide table{ width: auto !important; /* Adjusts table width */ } /* Change the background color to white for shaded rows (even rows) */ .remark-slide thead, .remark-slide tr:nth-child(2n) { background-color: white; } .remark-slide thead, .remark-slide tr:nth-child(n) { background-color: white; } </style> # .text-shadow[.white[Outline for Today]] <ol> <li><h4 class="white">Introduce you to the GHM paper</h4></li> <li><h4 class="white">Basics of "Difference-in-Differences"</h4></li> <li><h4 class="white">Summary of the results of GHM</h4></li> </ol> --- ## Next Week <svg viewBox="0 0 448 512" style="height:1em;display:inline-block;position:fixed;top:10;right:10;" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg"> <path d="M0 464c0 26.5 21.5 48 48 48h352c26.5 0 48-21.5 48-48V192H0v272zm64-192c0-8.8 7.2-16 16-16h288c8.8 0 16 7.2 16 16v64c0 8.8-7.2 16-16 16H80c-8.8 0-16-7.2-16-16v-64zM400 64h-48V16c0-8.8-7.2-16-16-16h-32c-8.8 0-16 7.2-16 16v48H160V16c0-8.8-7.2-16-16-16h-32c-8.8 0-16 7.2-16 16v48H48C21.5 64 0 85.5 0 112v48h448v-48c0-26.5-21.5-48-48-48z"></path></svg> 1. Economic development incentives 2. Economic development incentives briefing note 3. First quiz is on February 11th --- ## Readings <svg viewBox="0 0 576 512" style="height:1em;display:inline-block;position:fixed;top:10;right:10;" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg"> <path d="M542.22 32.05c-54.8 3.11-163.72 14.43-230.96 55.59-4.64 2.84-7.27 7.89-7.27 13.17v363.87c0 11.55 12.63 18.85 23.28 13.49 69.18-34.82 169.23-44.32 218.7-46.92 16.89-.89 30.02-14.43 30.02-30.66V62.75c.01-17.71-15.35-31.74-33.77-30.7zM264.73 87.64C197.5 46.48 88.58 35.17 33.78 32.05 15.36 31.01 0 45.04 0 62.75V400.6c0 16.24 13.13 29.78 30.02 30.66 49.49 2.6 149.59 12.11 218.77 46.95 10.62 5.35 23.21-1.94 23.21-13.46V100.63c0-5.29-2.62-10.14-7.27-12.99z"></path></svg> 1. .small[O'Flaherty (2005) (pages after 525 and after are optional reading)] 2. .small[Bartik (2017) just pages 1 to 5 (the "overview")] 3. .small[Briefing note readings:] 1. .small[Last Names A to D -> Neumark, Kolko - 2010] 2. .small[Last Names E to G -> Button - 2019] 3. .small[Last Names H to J -> Holmes - 1998] 4. .small[Last Names K to L -> Coates and Humphreys - The Stadium Gambit] 5. .small[Last Names M to O -> Moretti, Wilson - 2014] 6. .small[Last Names P to S -> Strauss-Kahn, Vives - 2009] 7. .small[Last Names T to Z -> Lee - 2008] --- class: segue-yellow background-image: url("assets/TulaneLogo.svg") background-size: 20% background-position: 95% 95% # Agglomeration Spillovers in Action <svg viewBox="0 0 640 512" style="height:1em;display:inline-block;position:fixed;top:10;right:10;" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg"> <path d="M616 192H480V24c0-13.26-10.74-24-24-24H312c-13.26 0-24 10.74-24 24v72h-64V16c0-8.84-7.16-16-16-16h-16c-8.84 0-16 7.16-16 16v80h-64V16c0-8.84-7.16-16-16-16H80c-8.84 0-16 7.16-16 16v80H24c-13.26 0-24 10.74-24 24v360c0 17.67 14.33 32 32 32h576c17.67 0 32-14.33 32-32V216c0-13.26-10.75-24-24-24zM128 404c0 6.63-5.37 12-12 12H76c-6.63 0-12-5.37-12-12v-40c0-6.63 5.37-12 12-12h40c6.63 0 12 5.37 12 12v40zm0-96c0 6.63-5.37 12-12 12H76c-6.63 0-12-5.37-12-12v-40c0-6.63 5.37-12 12-12h40c6.63 0 12 5.37 12 12v40zm0-96c0 6.63-5.37 12-12 12H76c-6.63 0-12-5.37-12-12v-40c0-6.63 5.37-12 12-12h40c6.63 0 12 5.37 12 12v40zm128 192c0 6.63-5.37 12-12 12h-40c-6.63 0-12-5.37-12-12v-40c0-6.63 5.37-12 12-12h40c6.63 0 12 5.37 12 12v40zm0-96c0 6.63-5.37 12-12 12h-40c-6.63 0-12-5.37-12-12v-40c0-6.63 5.37-12 12-12h40c6.63 0 12 5.37 12 12v40zm0-96c0 6.63-5.37 12-12 12h-40c-6.63 0-12-5.37-12-12v-40c0-6.63 5.37-12 12-12h40c6.63 0 12 5.37 12 12v40zm160 96c0 6.63-5.37 12-12 12h-40c-6.63 0-12-5.37-12-12v-40c0-6.63 5.37-12 12-12h40c6.63 0 12 5.37 12 12v40zm0-96c0 6.63-5.37 12-12 12h-40c-6.63 0-12-5.37-12-12v-40c0-6.63 5.37-12 12-12h40c6.63 0 12 5.37 12 12v40zm0-96c0 6.63-5.37 12-12 12h-40c-6.63 0-12-5.37-12-12V76c0-6.63 5.37-12 12-12h40c6.63 0 12 5.37 12 12v40zm160 288c0 6.63-5.37 12-12 12h-40c-6.63 0-12-5.37-12-12v-40c0-6.63 5.37-12 12-12h40c6.63 0 12 5.37 12 12v40zm0-96c0 6.63-5.37 12-12 12h-40c-6.63 0-12-5.37-12-12v-40c0-6.63 5.37-12 12-12h40c6.63 0 12 5.37 12 12v40z"></path></svg> --- ## Paper's abstract <svg viewBox="0 0 384 512" style="height:1em;display:inline-block;position:fixed;top:10;right:10;" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg"> <path d="M288 248v28c0 6.6-5.4 12-12 12H108c-6.6 0-12-5.4-12-12v-28c0-6.6 5.4-12 12-12h168c6.6 0 12 5.4 12 12zm-12 72H108c-6.6 0-12 5.4-12 12v28c0 6.6 5.4 12 12 12h168c6.6 0 12-5.4 12-12v-28c0-6.6-5.4-12-12-12zm108-188.1V464c0 26.5-21.5 48-48 48H48c-26.5 0-48-21.5-48-48V48C0 21.5 21.5 0 48 0h204.1C264.8 0 277 5.1 286 14.1L369.9 98c9 8.9 14.1 21.2 14.1 33.9zm-128-80V128h76.1L256 51.9zM336 464V176H232c-13.3 0-24-10.7-24-24V48H48v416h288z"></path></svg> > We quantify agglomeration spillovers by comparing changes in total factor productivity (TFP) among incumbent plants in “winning” counties that attracted a large manufacturing plant and “losing” counties that were the new plant's runner‐up choice. Winning and losing counties have similar trends in TFP prior to the new plant opening. Five years after the opening, incumbent plants' TFP is 12 percent higher in winning counties. This productivity spillover is larger for plants sharing similar labor and technology pools with the new plant. Consistent with spatial equilibrium models, labor costs increase in winning counties, indicating that profits ultimately increase less than productivity. --- ## Spillovers from agglomeration - Greenstone et al. (2010) try to measure the spillovers of agglomeration. - We talked about these earlier. Locating near other firms, especially of a similar type, can lead to benefits. - These benefits include: 1. Sharing similar intermediate input markets (labor, capital) that are “thick” markets, so it’s easier to find what you need. Costs of capital with high fixed costs (e.g., production studio) can be better shared among firms. Thick markets also allow a better match between employees and employers. 2. Spread of ideas, often through workers that move more frequently between firms or otherwise communicate often (“happy hour”, industry groups). - These spillovers will increase productivity. - Greenstone et al. (2010) seek to figure out what happens to existing manufacturing firms when a large manufacturing firm moves to the area. - How does the productivity of the existing manufacturing firms change? --- class: segue-yellow background-image: url("assets/TulaneLogo.svg") background-size: 20% background-position: 95% 95% # Selection Bias <svg viewBox="0 0 512 512" style="height:1em;display:inline-block;position:fixed;top:10;right:10;" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg"> <path d="M256 8C119.043 8 8 119.083 8 256c0 136.997 111.043 248 248 248s248-111.003 248-248C504 119.083 392.957 8 256 8zm0 448c-110.532 0-200-89.431-200-200 0-110.495 89.472-200 200-200 110.491 0 200 89.471 200 200 0 110.53-89.431 200-200 200zm107.244-255.2c0 67.052-72.421 68.084-72.421 92.863V300c0 6.627-5.373 12-12 12h-45.647c-6.627 0-12-5.373-12-12v-8.659c0-35.745 27.1-50.034 47.579-61.516 17.561-9.845 28.324-16.541 28.324-29.579 0-17.246-21.999-28.693-39.784-28.693-23.189 0-33.894 10.977-48.942 29.969-4.057 5.12-11.46 6.071-16.666 2.124l-27.824-21.098c-5.107-3.872-6.251-11.066-2.644-16.363C184.846 131.491 214.94 112 261.794 112c49.071 0 101.45 38.304 101.45 88.8zM298 368c0 23.159-18.841 42-42 42s-42-18.841-42-42 18.841-42 42-42 42 18.841 42 42z"></path></svg> --- ## What is selection bias? - Suppose I want to know the effect of a college degree on earnings. - I compare the earnings of people with a college degree to those without a college degree. - I find that people with a college degree earn more than those without a college degree. - Does this mean that a college degree causes higher earnings? - No, it could be that people who go to college are more motivated, smarter, etc. than those who don’t go to college. - This is called .red[selection bias]. - We need to control for these other factors that affect earnings. --- ## Example of selection bias .pull-left[ <img src="01-class1_files/figure-html/example1-1.png" width="80%" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] .pull-right[ <img src="01-class1_files/figure-html/example2-1.png" width="80%" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] --- ## Measuring the effect of agglomeration is hard - Suppose I looked at firms in Silicon Valley. - I would see that they’re all (mostly!) very productive. - Is this because of the benefits of agglomeration? - Or is it .red[selection bias], where the productive firms self-selected into Silicon Valley? Or these firms are just more productive anyways, and it doesn’t have to do with the benefits of agglomeration? - To capture the spillovers from agglomeration we need to separate the .red[selection bias] from the actual spillover effect. I will show you soon how .red[selection bias] could operate in the context of GHM and how they get around it. --- ## Measuring the effect of agglomeration is hard - Suppose that .red[selection bias] exists. - If this is the case, then we will get a biased estimate of the causal effect. - My estimate of the causal effect = actual spillover effect + selection bias - Depending on the context, .red[selection bias] could be positive, so I incorrectly overstate the causal effect, or it could be negative, so I incorrectly understate the causal effect. - To capture the spillovers from agglomeration I need to separate the .red[selection bias] from the actual spillover effect. GHM does this in a unique way using an approach called “Difference-in-Differences” that I will introduce you today. --- ## What are "causal effects"? - About half of economics research nowadays tries to quantify what are called .red[causal effects]. They try to find the .red[causal effect] for some policy or event. - .red[Causal effects] means: what is the actual effect of this policy or event on some outcome(s)? - Examples: - What is the effect of tax incentives for the film industry on filming location choice? - What effect do rent control policies have on rent prices and the supply of housing? - What effect do “ban the box” policies have on discrimination in hiring on the basis of criminal record, race, or ethnicity? - What effect do Section 8 housing vouchers have on families? - We call the these “causal effects” since we want to know how some exist or policy causes some sort of outcome. - We want an estimate that is “causal”, showing the effect of some X on some Y. --- ## What are "causal effects"? - We want to avoid an estimate that gives us simply a correlation. Many things can be correlated but not related through causation. - E.g., greenhouse gas emissions have risen over time at the same time that the number of people who are pirates decreases. This does not mean that the decrease in pirates is causing climate change! We also want to estimate the effect of a policy or program that controls for other things that could be going on. - E.g., Seattle could increase it’s minimum wage. After that Seattle could experience some change in employment (positive or negative). That could be due to the minimum wage or it could be due to something else that we haven’t controlled for. .pull-right[  ] --- ## What are "causal effects"? - The gold standard (i.e. the best approach) to estimate causal effects is through a randomized control trial (called an RCT). - This is done in the social sciences sometimes, but it’s more common in medicine. - For example, a common RCT is studying the causal effect of a drug on some sort of health outcome(s). - Researchers will randomize subjects (people) into a treatment or control group. The treatment group gets the pill (called the “treatment”) and the control group gets a placebo. - Since the treatment and control groups are on-average identical due to the randomization, any differences in outcomes between the two groups is due to the treatment (the pill). --- ## What are "causal effects"? - While social scientists can sometimes randomize “treatments” to study their effects (we will see a few examples), often time it’s not possible to use an RCT to estimate causal effects. - For example, it is unethnical or not feasible to randomize things like state laws. It would be lovely, from an estimation standpoint, to randomize, say, which states have tax credits to see what effect tax credits have, but it’s just not possible. - Social scientists often have to use other methods to try to get an estimate of something close to the true causal effect. - One such method we will discuss is the “Difference-in-Differences” (aka Diff-in-Diff, DiD, or DD), which is incredibly common in economics and also in the quantitative social sciences. - The DiD approach gives us a causal estimate of some policy or event X on some outcome Y, but under certain assumption only. --- ## What do Greenstone et al. (2010) do? - GHM look at large manufacturing firms (“million dollar plants” or MDPs) that chose to set up in certain counties (“winner” counties). - They then use information to determine their runner-up (loser) counties. They determine what the loser counties are by using published information in the corporate real estate journal Site Selection. - In Site Selection they published an article in each issue called “Million Dollar Plants”. - Each article mentions the winning county and the loser counties. - This gives then a “treatment group” (the winning counties) and a set of “control groups”) (counties that just barely did not win the MDP). - GHM compare other, existing manufacturing firms the winning county to existing manufacturing firms in the counties that just barely lost out on getting the MDP. - Firms in the winning county = “treated” group -> these firms gets the agglomeration spillovers from the large firm that moves in. - Firms in the losing counties = “control” group -> these firms do NOT get the spillovers. Similar to a randomized trial (e.g., a study of the effects of a drug). --- ## Are the "losers" a good control group? - A fundamental assumption is required to get a proper estimate of the actual (causal) effect of spillovers. - The treatment group (firms in winning county) must be as close as identical as possible to the control group (firms in losing counties). - Why might this not hold? - Winning counties might be better. Firms in winning counties might be more productive, independent of the spillover effect from the new firm. - For this reason they use a “difference-in-differences” methodology. --- class: segue-yellow background-image: url("assets/TulaneLogo.svg") background-size: 20% background-position: 95% 95% # Intro to Difference-in-Differences --- ## A Brief Intro to Difference-in-Differences - Also called “Diff-in-Diff” or just DD or DID or DiD. - This is a particular model used in regression analysis (more on what that is later). - Instead of just comparing the “treated” firms (firms in the winning county) to the “control” firms (firms in the losing counties), they make this comparison over time. - Compare the pre-period (the large firm hasn’t moved in yet, no firm is “treated”) to the post-period (the large firm has moved in, only firms in the winning county are “treated”) --- ## How does DiD work? <img src="01-class1_files/figure-html/did-table-ex-1.png" width="80%" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> --- ## The Difference-Difference Estimate - Step 1: Take the before and after difference for the firms in the winning county: A – B - Where A = productivity of existing firms in winning counties AFTER the MDP plant moves in. - B = productivity of existing firms in winning counties BEFORE the MDP plant moves in. - Step 2: Take the before and after difference for the firms in the losing counties: C – D - Where C = productivity of existing firms in losing counties AFTER the MDP plant moves into the winning county (but not the losing counties). - D = productivity of existing firms in losing counties BEFORE the MDP plant moves in. - Step 3: Take the difference-in-difference (hence the name). - The difference-in-differences estimate of the causal effect is: (A – B) – (C – D) - That is, the before vs after in winning counties (A – B) compared to the before vs after in losing counties (C – D). --- ## The Difference-Difference Estimate - The difference-in-differences estimate of the causal effect is: (A – B) – (C – D) - The A – B tells us the change over time in the winning county. How did productivity change for existing firms? - The C – D tells give us an estimate of the counterfactual. If winning counties are similar to losing counties in their economic trends (we will get into that) then C – D gives us an estimate of what would have happened without a MDP moving in. --- ## The Difference-Difference Estimate: Plot <img src="01-class1_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-3-1.png" width="80%" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> --- ## DiD vs “Naïve Comparisons” To better illustrate how DiD can estimate causal effects better than other comparisons, consider two “naïve” comparisons: 1. Naïve comparison 1: No control group (A – B) 2. Naïve comparison 2: No pre-period (A – C) --- ## Naïve Comparison 1: No Control Group - Suppose I didn’t have a control group, and I decided just to compare the treated group before and after. - That is, I compare the productivity of the existing firms in the county that wins the MDP before the MDP arrives (“B”) to the productivity of the existing firms in the county that wins the MDP after the MDP arrives (“A”). - That is, I calculate A – B and use that as my estimate of the effect of spillovers on productivity. - The problem with using A – B as the estimate is that it could include bias from **uncontrolled time trends**. - Time trends = an existing trend where the outcome variable would have decreased or increased anyways, independent of the effect of the “treatment” (MDP moving in). - The estimate A - B does not control for these existing time trends, and it could overstate or understate the true causal effect. --- ## Naïve Comparison 1: No Control Group - Example of overstating the effect (upwardly/positively biased estimate): - Suppose that productivity was growing in the county anyways before the MDP moved in. Or, the MDP selected that county because it was experiencing productivity growth. - Therefore, if we use A – B as our estimate, it might overstate the effect of spillovers, attributing the increase that would have happened anyways to the treatment (the MDP moving in). -- - Example of understating the effect (downwardly/negatively biased estimate): - Suppose that productivity was decreasing in the county anyways before the MDP moved in. - Therefore, if we use A – B as our estimate, it might understate the effect of spillovers. The estimated effect would be the actual effect + the productivity change that would have happened anyways (negative in this example). --- ## Naïve Comparison 2: No Before Period - Suppose I did have a control group, but I didn’t have or use data from before the MDP moved in. - That is, I compare the productivity of the existing firms in the county that wins the MDP after the MDP arrives (“A”) to the productivity of the existing firms in the counties that do not win the MDP in the same period (“C”). - That is, I calculate A – C and use that as my estimate of the effect of spillovers on productivity. - The problem with using A – C as the estimate is that it could include bias from **uncontrolled differences between groups**. - Differences between groups = groups (e.g., existing firms and winning and losing counties) are on-average different, such as having different existing productivity levels. - The estimate A - C does not control for these existing group differences. It’s not an “apples to apples” comparison because the treatment group and control group are not on-average the same. - This means that A – C could be either positively or negatively biased depending on the differences between groups. --- ## Naïve Comparison 2: No Before Period - Example of overstating the effect (upwardly/positively biased estimate): - Suppose that the existing firms in the winning counties are on-average more productive. It may be that the MDP chose to go to that winning county for that reason. - Therefore, if we use A – C as our estimate, it might overstate the effect of spillovers, attributing the differences as due to the benefits of spillovers, when really that difference captures the benefits of spillovers plus the average difference between groups. -- - Example of understating the effect (downwardly/negatively biased estimate): - Suppose that the existing firms in the winning counties are on-average less productive. - Therefore, if we use A – C as our estimate, it might understate the effect of spillovers, attributing the differences as due to the benefits of spillovers, when really that difference captures the benefits of spillovers plus the average difference between groups. --- ## DiD removes (some) sources of bias DiD removes two sources of bias: 1. Existing time trends -> under the assumption the control group tells you the counterfactual, what would have happened had treatment not occurred, then DiD removes the existing time trend. 2. Existing fixed differences between groups -> The use of data before and after the treatment (MDP moving in) allows researchers to subtract out the fixed differences between the treatment and control group. - However, DiD could still give a biased estimate if an important assumption, called the parallel trends assumption, does not hold. --- ## Parallel Trends Assumption - This assumption must be true for the DiD to provide an unbiased estimate of the causal effect. - .red[Parallel trends assumption] = The assumption that, had treatment not occurred (the MDP actually didn’t move in), then the treatment group and control group would have had the same changes in productivity over time (i.e. parallel changes). - I am going to rephrase this several times as rephrasing this might make it more understandable. <img src="01-class1_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-4-3.png" width="50%" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> --- ## Parallel Trends Assumption - Another way to phrase this assumption is that the control group is a correct estimate of the counterfactual. - Counterfactual = what would have happened to the existing firms in the winning county, had the MDP not moved in. - We do not know this counterfactual. For us to know it, we would have to observe a universe both where the MDP moved in and one where it did not. - Since we only observe either the MDP moving in, or not moving in, we use the control group to **estimate** the unobserved case. -- - Another way to phrase the parallel trends assumption is that the control group gives an accurate estimate of the “business as usual” – what would have happened to those firms without the MDP moving in. - The counterfactual estimate (C – D) gives us the change we would expect in the outcome variable anyways, independent of the “treatment” (the MDP moving in). --- ## Violations of Parallel Paths Violations of the Parallel Paths assumption lead the DiD estimate to be biased. Examples: 1. Suppose that the control counties had existing productivity growth that was slower than the existing growth trend in the treated county(ies). Then my DiD estimate would overstate the true causal effect, since my estimated counterfactual growth rate of productivity would be too small. 2. Suppose that something happens over time that is not controlled for that affects either the treatment of control group, or affects one differently than the other. 1. E.g., suppose that the MDP moves in at the same time that the county cuts taxes for all businesses. This means that existing productivity trends, that are independent of the MDP moving in, may be different since there is this uncontrolled event. 2. In this case, the DiD estimate would also likely overstate the true causal effect, with the DiD estimate being the causal effect + the effect of the tax cut --- ## Investigating Parallel Trends How do we know if Parallel Trends holds? 1. Check to make sure that nothing else happened over the same time period. Maybe taxes were cut in the winning counties before the firms moved in? 2. Look at pre-trends. Look at the trends in productivity in the winning and losing counties before the new firm enters. Did they seem to trend similarly? If they weren’t then that might suggest that parallel trends doesn’t hold. --- ## Investigating Parallel Trends <img src="01-class1_files/figure-html/prallel-trends-5.png" width="80%" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> -- How would this work in Greenstone el al. (2010)? 1. Seems unlikely that something happened in the winning counties before firm entry, relative to the losing counties. 2. They look at the pre-trends and note that they are similar for the firms in winning and losing counties. - This seems to suggest that parallel trends holds. --- ## Ok, so what exactly do they do? - Greenstone el al. (2010) use the difference-in-differences strategy to measure productivity spillovers on existing firms when the new firms enter the winning counties. - They use “total factor productivity” to measure productivity of the existing firms. --- ## Total Factor Productivity and Production Functions - Total factor productivity (TFP) is a measure of how efficiently inputs are used to produce output. - Going back to the Cobb-Douglas Production Function… $$ Y = A K^{\alpha} L^{1-\alpha} $$ Where: - Y = Output - K = Capital - L = Labor - A = Total Factor Productivity -> usually though of as technology or production practices. - Measures how much you can get out of fixed inputs (K and L constant). - E.g., hold K and L fixed. Double A, then Y doubles. Making double output with the same inputs. -- - Greenstone et al. (2010) use the “augmented” Cobb-Douglas production function to model the production (and productivity) of each firm. - Augmented as in, they used a more complicated model than the one earlier. - They use “A” to measure productivity. --- class: segue-yellow background-image: url("assets/TulaneLogo.svg") background-size: 20% background-position: 95% 95% # Results of Greenstone et al. (2010) <svg viewBox="0 0 512 512" style="height:1em;display:inline-block;position:fixed;top:10;right:10;" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg"> <path d="M496 384H64V80c0-8.84-7.16-16-16-16H16C7.16 64 0 71.16 0 80v336c0 17.67 14.33 32 32 32h464c8.84 0 16-7.16 16-16v-32c0-8.84-7.16-16-16-16zM464 96H345.94c-21.38 0-32.09 25.85-16.97 40.97l32.4 32.4L288 242.75l-73.37-73.37c-12.5-12.5-32.76-12.5-45.25 0l-68.69 68.69c-6.25 6.25-6.25 16.38 0 22.63l22.62 22.62c6.25 6.25 16.38 6.25 22.63 0L192 237.25l73.37 73.37c12.5 12.5 32.76 12.5 45.25 0l96-96 32.4 32.4c15.12 15.12 40.97 4.41 40.97-16.97V112c.01-8.84-7.15-16-15.99-16z"></path></svg> --- ## Winning counties have higher productivity - Five years after the new manufacturing plants open in the winning counties, total factor productivity (TFP) is 12 percent higher in winning counties (relative to before, relative to losing counties). - Pretty big effect! - Greenstone et al. (2010) also found that the spillover effect was larger for firms that shared similar labor and technology pools with the new plants. This makes sense. --- ## What about labor costs? .pull-left[ - But something else happens. Labor costs increase. - This makes sense. A big manufacturing plant moves into the country. Demand for manufacturing works goes up. - Labor demand curve shifts to the right. - The wage increase should be higher in the short term than in the long term. - In the long term, more workers can move to that country (supply shifts right). ] .pull-right[  ] --- ## Total Effect on Existing Firms - Total Factor Productivity for existing firms increases by 12 percent over five years. - But labor costs also increase. - So part of the profit increase that would come from the TFP increase is eaten by labor costs.